The Horrors of Iodine Deficiency Disorders

Robert Tyabji, New Delhi, 1984. Updated April 2020

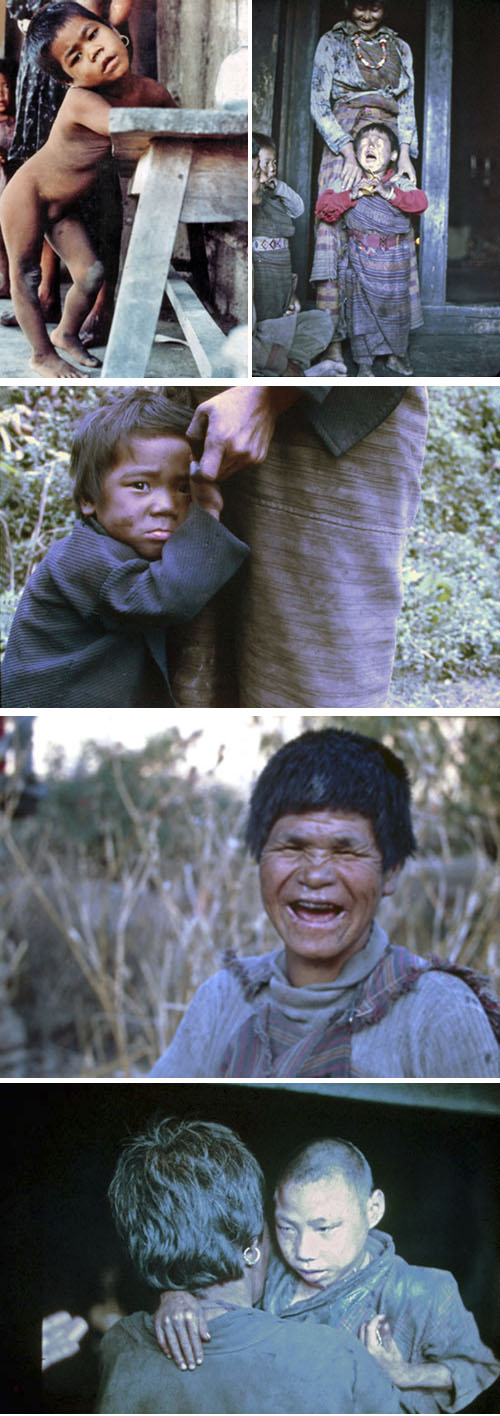

I shot these photos in 1983/84 to illustrate the seriousness of the iodine deficiency problem in Bhutan, as part of the preparations for establishing the UNICEF-assisted Iodine Deficiency Disorders Control Programme.

Background

Soils lacking iodine exist in mountainous regions as well as densely populated plains and river basins which are blighted by periodic flooding. In Asia alone, more than 50 million people live in these regions; consequently, in Asia, nearly a tenth of the human race is exposed to the risk of iodine deficiency disorders.

The function of the thyroid gland and its dependence on iodine intake became known only at the end of the nineteenth century. The gland needs iodine to produce thyroxine, a hormone essential for the growth and development of the body, and particularly the cells of the brain.

If a pregnant woman is starved of iodine, the foetus cannot produce enough thyroxine and foetal growth is retarded. Hypothyroid foetuses often perish in the womb and many infants die within a week of birth. If hypothyroid children survive they remain intellectually subnormal and may also suffer physical impairments. They lack the aptitudes of normal children of similar age and are often incapable of completing school.

Iodine deficiency is so easy to prevent that it is a crime to let a single child be born mentally handicapped for that reason - UNICEF Exectutive Director, 1978

The awful effects of iodine deficiency can be prevented by regularly consuming salt fortified with iodine, or by administering iodine rich oil (a more effective method over the medium term but also much more difficult and expensive). So why salt? Because every human being requires some salt - about 5 grams a day - in the diet. Some of this comes naturally from foods but a certain amount of salt needs to be added to make it palatable. When iodine is added to salt - 15 parts per million in practice - humans will derive the needed 150 micrograms of iodine per day to ensure adequate nutrition for normal growth and development.

In July of 1984 my assignment in Bhutan ended and I was transferred to the UNICEF Regional Office for South and Central Asia (ROSCA) in New Delhi. It was to be an interim assignment pending my transfer to another country office. My mandate in New Delhi was to develop the communication component of UNICEF's new pan-Asian IDD control programme.

As part of this work I wrote a book entitled The Use of Iodated Salt in the Prevention of Iodine Deficiency Disorders: A Handbook of Monitoring and Quality Control.

Goiter is a clear indication of iodine deficiency

Cretinism, a horrible outcome

These are victims of iodine deficiency. They face lifelong dependence on family, community and society. In some villages of Bolivia and Bhutan, up to a third of the population were cretins. In large areas of India and central Africa, 5 per cent of infants were born mentally retarded.

Theirs is a world of incomprehensible shadows. Severely retarded mentally, they may never speak, are stunted and many may never walk. Who knows what they see? They represent a quarter of the world’s children at risk of iodine deficiency, known to be the world’s leading cause of preventable mental retardation.

Is there a future? Cretin children are innocent victims of neonatal hypothyroidism brought on by a deficiency of iodine in their mother’s diet. They represented a moral and economic problem of vast magnitude where iodine deficiency was prevalent; in the Andes, in much of Africa, in a swathe extending from the Middle East through the “goitre belt” of the Himalaya to south-east and eastern Asia and in pockets of Australia and Europe.

The horrors of a cretin’s life can never be comprehended, yet they could have been prevented. Later generations in countries which have been implementing iodine supplementation programmes need never suffer this age-old scourge.