Journey to the Attic of the World, September 1998

Robert Tyabji, New Delhi, December 1998

Find a Sardarji (Sikh) self-taught motorcycle surgeon with magical skills; take two brand-new 1942 BSA 500 motorcycle engines bought as part of a job lot of scrap auctioned from a warehouse in Old Delhi; add two amateur adventurers from UNICEF and a plucky University student, all with a taste for the unusual and untried: and head for the hills!

It was September 1998 in Delhi when my friend and UNICEF colleague Peter Godwin, and Vikram from Delhi U, and I, unexpectedly found ourselves in the above situation.

"Kaka" Singh had taught himself the science and art of motor-cycle surgery by rebuilding his brother-in-law’s bike which had been squashed in an accident. Kaka had already earned a reputation for himself on the Delhi motorcycle stage when Peter and I got to know him through his elder brother, Avtar Singh, who had been working with me at UNICEF on projects like developing filmstrip production kits for village health workers and multi-purpose windmills for rural communities.

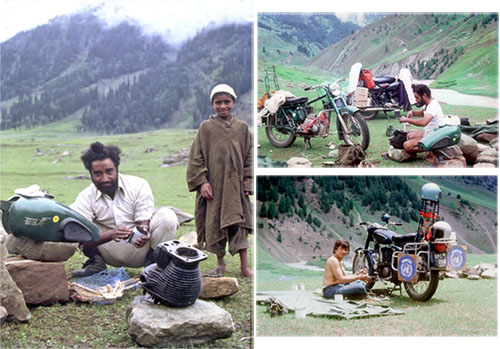

While trawling the used parts market, Kaka had found a cache of 1942 BSA 500cc side valve military-issue motorcycle engines, in their original packing, and I got the bright idea of putting together the superstructure of pre-war BSA frames with the front fork and rear swing arm sections of modern Enfield frames - primarily to provide good suspension in the rear (rather than simply the two springs under the saddle which is all the old BSAs had) while substantially improving maneuverability, stability and road-holding. Soon, encouraged by us, Kaka had built not one, but two very excellent machines.

Believe me, these were stunning bikes: solid, ultra-reliable and gorgeous to boot. The side valve BSA engines, designed originally for military use in the desert, were virtually unstoppable and indestructible, and the hybrid frames felt nearly as comfortable, balanced and safe as the BSA Gold Star touring bike I had previously owned. Coupled with tuned exhaust pipes and silencers, these engines idled at astonishingly low speed producing a lazy thump no modern bike could hope to match, yet one had only to open the throttle a bit to hear and feel what I can only describe as a combination of a purr and a roar.

Peter and I now began looking for ways to test the machines to see if they were really as good as they seemed. Soon an opportunity presented itself in the form of a government announcement that the military road over the high passes between the Kashmir Valley and Ladakh, the vast highland region of India bordering Tibet, would be opened to the public in May 1978. This was a challenge with great appeal, for what better test of mechanical (and human) performance could there be? Besides, each of us had other reasons for visiting Ladakh, but more on that later.

Kaka was aghast when it was suggested that he prepare four bikes and ride with the three of us to Ladakh!

It was obvious that he thought we'd gone completely cuckoo -- after all, no one had ever undertaken such a trip before, travelling unescorted into Kashmir where political problems were mounting, where one had to ride through dodgy areas bordering both Pakistan and China (neither of whom Indians considered trustworthy at the time) on one of the highest roads in the world which climbed treacherously through a 14,000-foot (4200 m) pass. Besides, winter was imminently around the corner so the road would be closed by snow and ice by the end of October, there were no services along the way, no workshops and spare parts, possibly no fuel and who knows, probably no proper food or accommodation...

But after much coaxing, Kaka grudgingly relented. He was fully aware that he would be our insurance against almost certain mechanical failure and that his skills and experience as a motorcycle doctor would be strained to the max, but he was too kind a guy to disappoint us. Probably our enthusiasm was infectious enough to convince him but I suspect that, deep down, he really wanted to be a part of the adventure!

I had already bought my bike from Kaka and it only needed fitting out to carry additional packs and the special equipment I intended to take along. Peter bought the second BSA hybrid from him, fitted with extra panniers and carriers to accommodate backpacks, sleeping bags, fuel, cookware and other essentials. Kaka and Vikram already owned Royal Enfield Bullets (350 cc) so these were tuned, fitted out and readied for the trip.

Each of us had his own agenda and set of expectations. Kaka just hoped to be able to do whatever damage control was necessary to return to Delhi in one piece and as quickly as possible. Vikram needed to sort out personal issues and wanted time and space away from home for reflection. For Peter and me, besides the expected adventure and thrills, visiting such a remote region where communities were still unsullied by development represented a unique chance to test and develop projects we were working on at UNICEF.

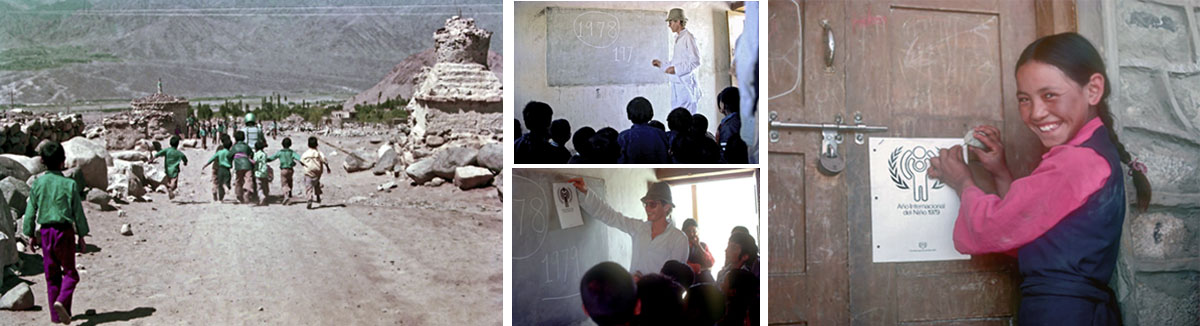

For you to appreciate the kind of the work we were doing at the time, I should mention that the following year, 1979, had been declared the International Year of the Child (IYC) during which UNICEF in every country was to highlight the situation of children in the context of their human rights. Every child is born with fundamental rights which cannot be revoked. These rights are enshrined in the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and are part of international law. Every government, and by extension every community, family and individual is responsible to ensure that these rights are fulfilled. By advocating these issues on the world stage, UNICEF expected that governments would be urged to allocate a greater share of national resources to children and introduce the legislation and programs needed to implement CRC. Furthermore, countries which had not already signed and ratified CRC would be prevailed upon to do so.

Peter was developing IYC posters and other UNICEF communication materials which he wanted to pretest with Ladakhi children.

I was working on two technical projects -- a solar-powered radio for classrooms and a self-contained kit for making slides and filmstrips for use by community workers and extension staff. The battery-less radio had a special acoustic chamber so it would be loud and clear enough for a full classroom, yet it was designed to work with the very low amount of electrical energy from a small solar panel. I was keen to test the radio in Ladakh's extreme climate. I also wanted to train government health and community development field staff in the use of the filmstrip kit and at the same time test its film processing chemistry under local conditions.

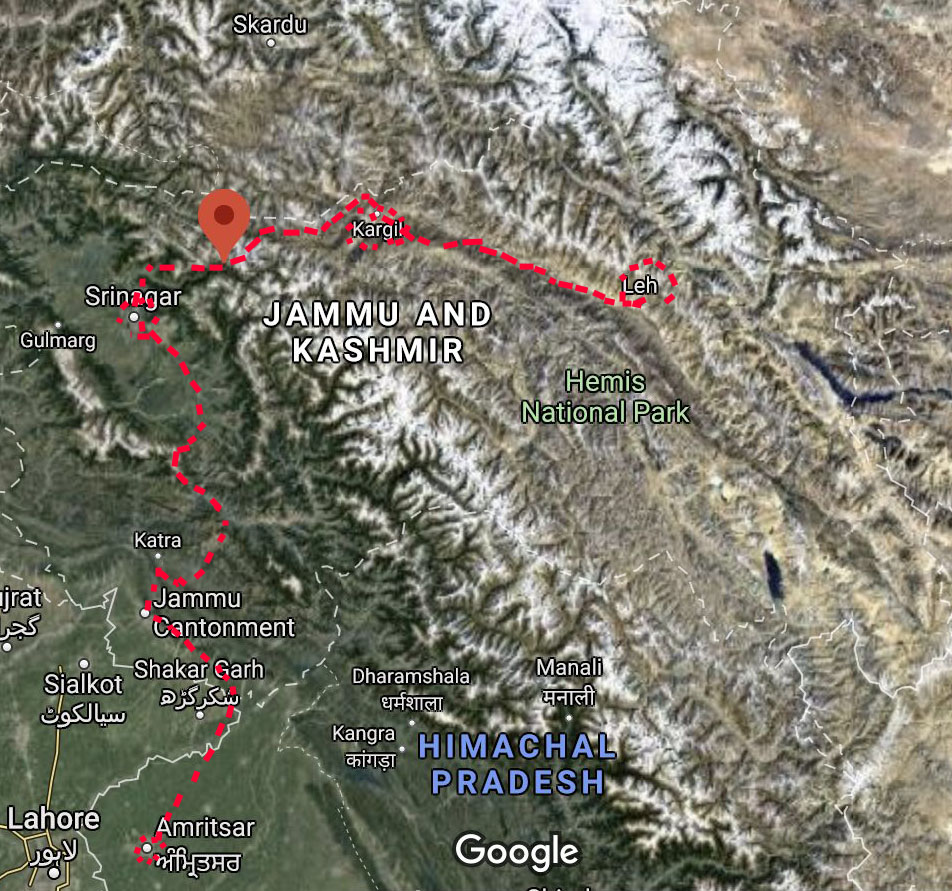

In mid September the four of us - Peter, Vikram, Kaka and I - were at last ready to embark on the approximately 2200 Km return trip to Leh, capital of Ladakh district in Kashmir. It was necessary to start as early in September as possible so we'd have enough time to complete our business in Kashmir and Ladakh and still leave a reasonable margin for breakdowns, landslides, road closures and other delays beyond our control. Also, the Indian army had made it clear that they would close the mountain passes in late October and we certainly didn't relish the idea of being stuck in Ladakh till spring five months later!

The route took us north through Amritsar in Punjab, Jammu in Jammu and Kashmir State, and over the Banihal Pass to Srinagar in the Kashmir valley. We stopped for a couple of days in Srinagar to meet friends and for me to liaise with the Kashmir government. In addition, Hootoksi had flown up to be with me for a few days. Heavily pregnant with Adil, the lure of an exciting holiday in India's most beautiful region was irresistible, and she even risked riding pillion with me!

The route took us north through Amritsar in Punjab, Jammu in Jammu and Kashmir State, and over the Banihal Pass to Srinagar in the Kashmir valley. We stopped for a couple of days in Srinagar to meet friends and for me to liaise with the Kashmir government. In addition, Hootoksi had flown up to be with me for a few days. Heavily pregnant with Adil, the lure of an exciting holiday in India's most beautiful region was irresistible, and she even risked riding pillion with me!

Here I had a chance to train a trio of government health extension workers in the use of the Filmstrip Kit. It also gave me the opportunity to do a reality check of the Kit's chemical monobath formulation using raw river water to process and develop the filmstrips. As it turned out, the health staff produced an excellent filmstrip starring local children!

Peter noticed that his bike had been overheating, so Kaka used the break in Sonamarg to dismantle the engine and polish the piston. This solved the problem and Peter's bike never broke a fever again. And I had some time to check out my bike and ensure that the solar panel behind my seat was charging the battery properly.

After Hootoksi left to return to Delhi, we checked our gear for the coming task of crossing the high mountain passes that separate Ladakh from the Kashmir valley. In addition to our clothes, camping gear and the UNICEF solar radio and panel, we had to stow food and water, basic cooking utensils, tools, fuel, spare parts, small gifts for the children, and firewood. All this was stowed in our bikes' panniers and carriers, leaving no extra room on the seats behind us.

After Hootoksi left to return to Delhi, we checked our gear for the coming task of crossing the high mountain passes that separate Ladakh from the Kashmir valley. In addition to our clothes, camping gear and the UNICEF solar radio and panel, we had to stow food and water, basic cooking utensils, tools, fuel, spare parts, small gifts for the children, and firewood. All this was stowed in our bikes' panniers and carriers, leaving no extra room on the seats behind us.

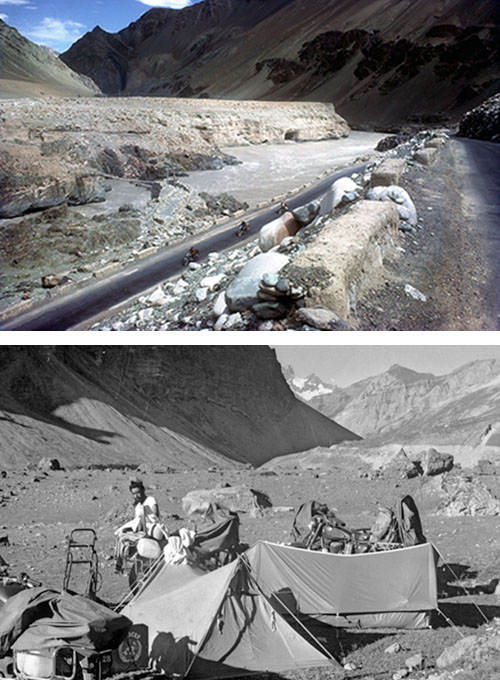

The first night after traversing the stunningly beautiful Dras Valley where the road was carved out of rocks and piles of snow, we set up camp in a clearing by the roadside. The night was clear, still and chillingly cold but sitting on our camp stools under a canopy of stars with a fire going and glasses or rum in hand was an experience I shall always remember.

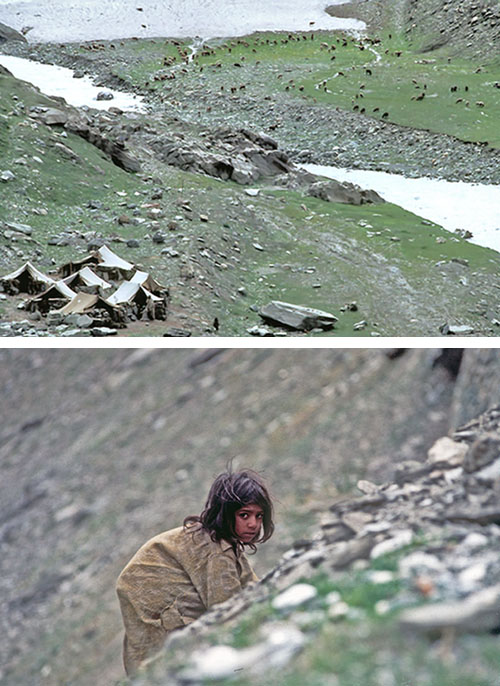

Somewhere between Dras and Bhimbat I spotted a gypsy camp with flocks of sheep in a valley far below. We stopped to make tea and some gypsy kids who'd seen us scampered up the mountainside to stare at us in awe. Perhaps they'd never seen such an apparition before!

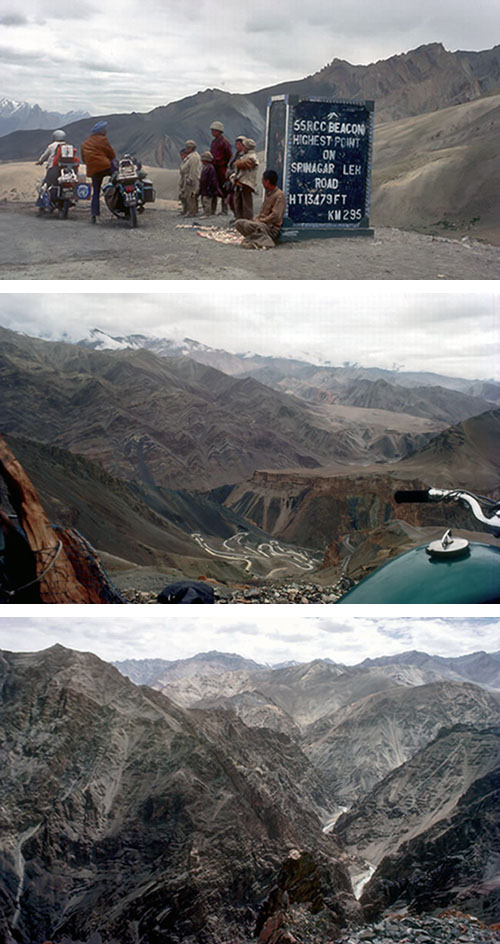

We rested briefly at the highest point on the road, 13,479 ft above sea level, and stopped occasionally to gaze and marvel at the views of the winding road, the mountains and the mighty roaring Indus River far below.

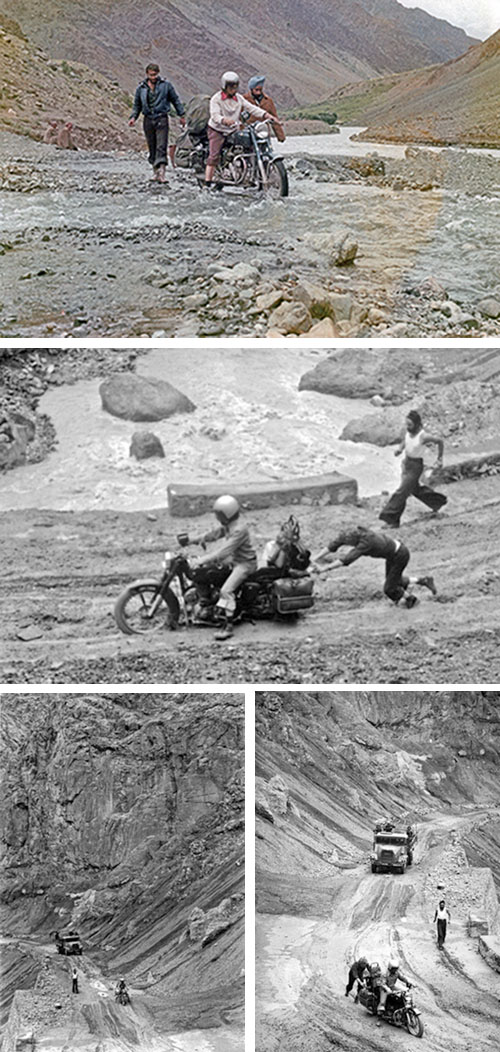

Closer to Leh, there were long stretches of road alongside the rocky shores of the Indus, an immense cascade of churning white water. Many parts of the road surface were completely eroded and muddy so it was impossible to traverse some of them on our own power. At one point a couple of French photographers travelling in their Volkswagen camper studio stopped and towed us through the mud. At other times, we had to take turns to push each other through.

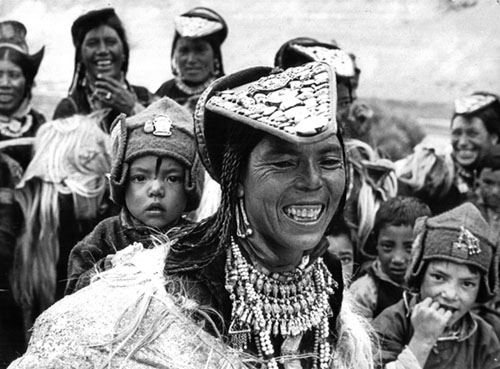

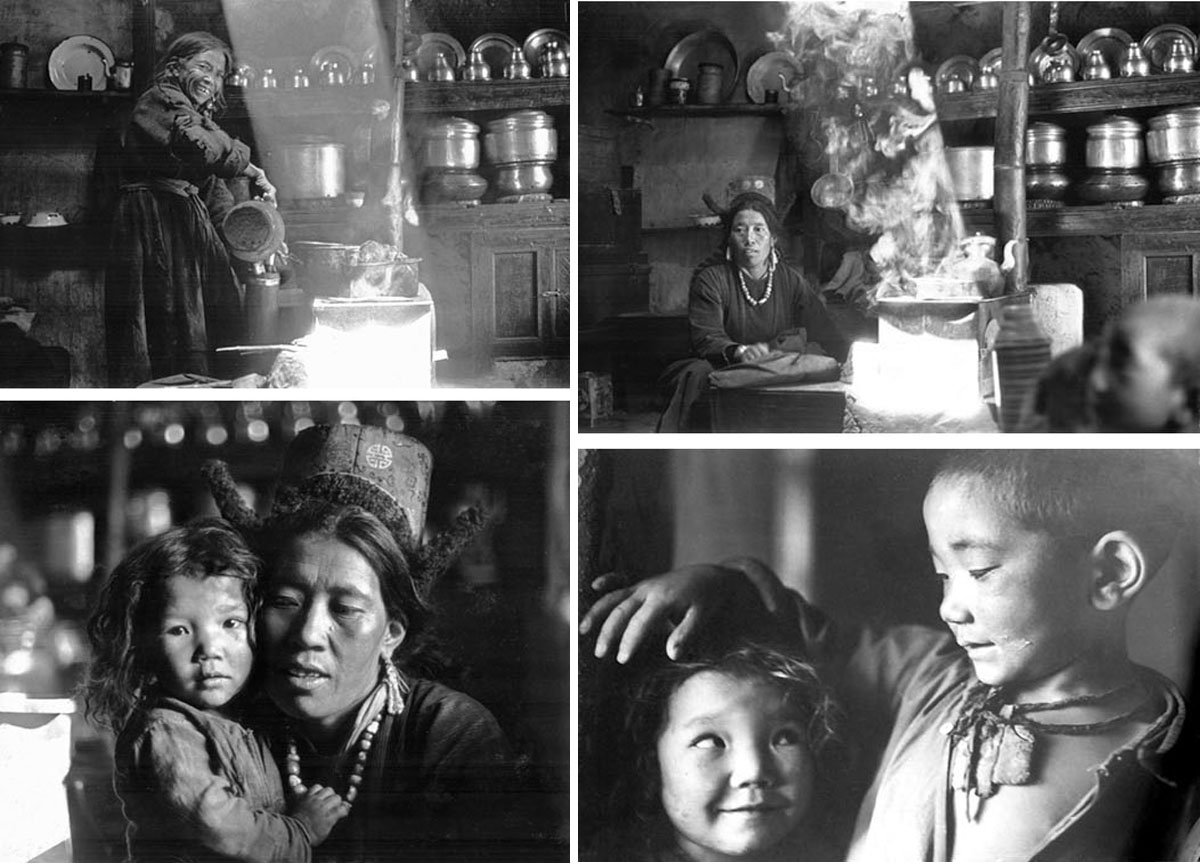

As luck would have it, we happened upon a festive community event in one of the villages we visited along the way. The women were out in their traditional finery - their colourful kuntops and goatskin-backed shawls and ornamental headwear studded with semi-precious stones, their young children slung in the shawl or carried in baskets. The men wore their gouchas (similar to the Bhutanese gho) and perak top hats.

I got to meet a particular family and was honored to be invited to their home for gurgur cha (butter tea - local tea leaves made in yak milk and yak butter and thoroughly mixed in a traditional churner, a tall wooden cylinder with a plunger).

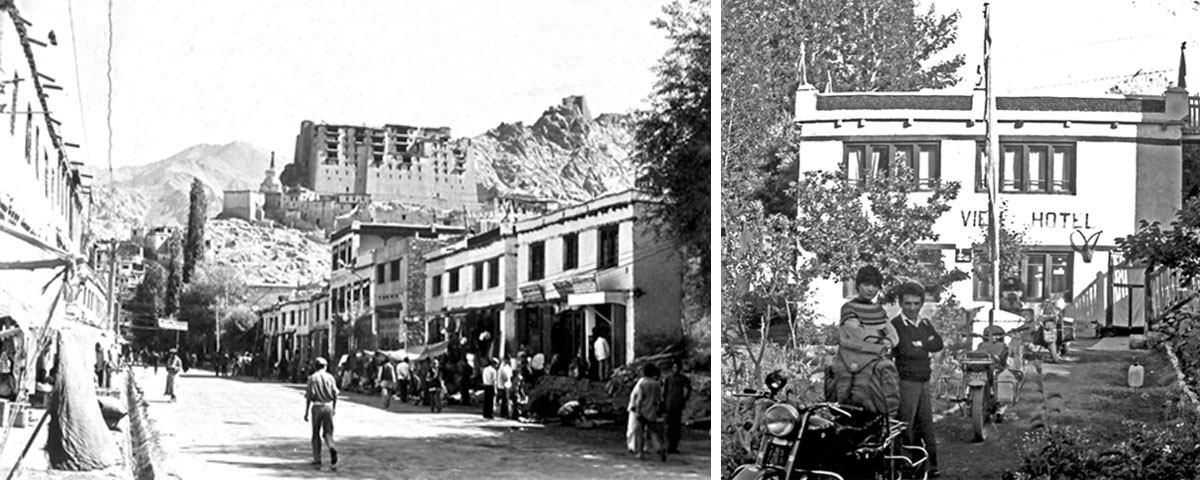

Leh, the state capital, was a sleepy little town with one main street with shops selling local produce and sundries. As the military road to Ladakh had been opened to public traffic for the first time just a few weeks before, and visitors arriving by air were few, there was just one hotel for us. The staff welcomed us warmly, set us up comfortably and made sure we were well fed with delicious Ladakhi snacks and dishes.

The government education department designated a rural school near Leh for the solar radio trials. Here, Peter had the opportunity to promote the upcoming International Year of the Child and field test the communication materials he had developed.

Later, we all agreed that that trip was unforgettable and that it would not be the last. However, that was not be be as our lives took different paths - Vikram tragically passed away a few months later, Peter got married and moved to Kenya, Kaka became engrossed in making and exporting spare parts to America for enthusiasts of Indian motorcycles (which had become obsolete in the sixties) and I moved with the family to Bhutan.

I close with some memories of our return trip.