Chasing Windmills!

Robert Tyabji

MULTIPURPOSE WINDMILL, RAJASTHAN

In 1985/86 I spent a lot of time at Bunker Roy’s Social Work and Research Centre in Tilonia, near Ajmer in Rajasthan, about a 5-hour drive from my (UNICEF) office in New Delhi.

The organization, now better known as The Barefoot College, has since grown into a renowned rural institution of learning and innovation in India and abroad. My purpose in visiting them was to field test prototypes of the UNICEF filmstrip kit among farmers and rural extension workers. At the time, I had no idea that fresh ideas would come to me and that a new project would take root there!

Bunker’s team spared no effort to provide basic creature comforts for the resident staff as well as visiting researchers and guests such as myself and the lifestyle and culture at SWRC were completely in harmony with the rest of rural Rajasthan. Meals were communal, water came from the well, electricity was sporadic and one either walked or used a bicycle to get around. It was a wholesome experience and I would seize every opportunity to make the 5-hour drive to Tilonia, often taking the family along. Hootoksi loved working with the village women and children while I worked, and the boys would disappear into the surrounding hills for hours. There, new ideas would come to me as if by magic and I could to do some serious thinking and reality checking while thoroughly cleansing myself of the Delhi vibe.

On one such visit in 1974 I became intrigued by the possibility of using nature’s energies to help villagers with everyday tasks like drawing water and grinding grain. These chores were usually carried out by women but demanded enormous effort and allowed them no time to engage in more productive and enlightening activities such as attending literacy classes or learning a skill or trade.

It was obvious to me that a windmill could harness the breezes that wafted daily through Tilonia. I was intrigued by the idea of inventing a multipurpose wind machine capable of powering devices such as water pumps, grain grinders, fodder choppers and electric generators. For many women, such a machine would ease the endless cycle of chores and give them new-found opportunities to avail of the social and educational services offered by SWRC. When I mentioned this over dinner in that June of 1974, Bunker was enthusiastic and promised to consider funding such a windmill as part of SWRC’s appropriate technology programme.

Nowhere in India (or anywhere else for that matter) could I source a windmill capable of doing the kind of work needed in Tilonia. Even the farm wind-pump commonly seen in the US and Australian countryside would have had to be imported, at prohibitive cost. Besides, such windmills were designed to work reciprocating pumps (i.e. pumps with a rod that had to be repeatedly lifted and pushed down) and so could not efficiently turn agro-industrial machinery like grinding wheels, choppers and deep freezers. This meant that a completely different type of windmill had to be designed with a rotary drive that could be readily linked to such machines. It would need to be built locally out of common materials, should be repairable by local mechanics and should cost much less than a commercial windmill. This was a challenge close to my heart!

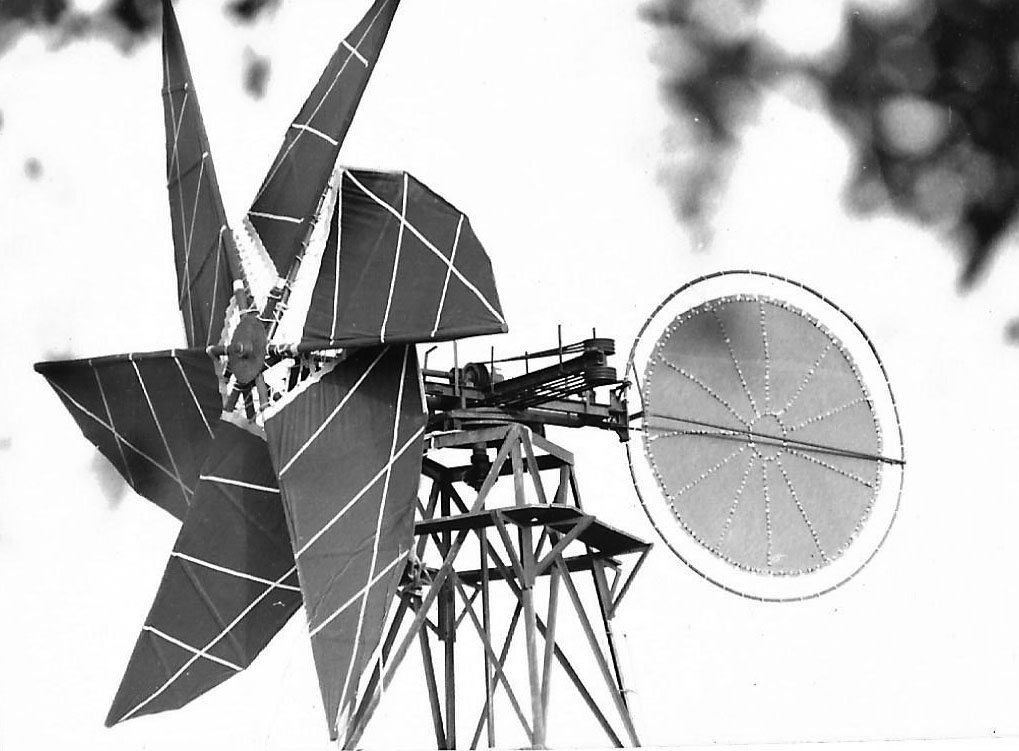

The prototype took me a year and a half to design and build. For the technically minded, I designed a 16-foot diameter rotor with six canvas blades shaped like a yacht’s sail and pitched at an angle of 8 degrees.

Harnessing Wind Power for Rural Development - read the article (Invention Intelligence Special Number on Technology for the Masses, National Research Development Corporation of India, January-February 1977.

The large circular tail fin was also stretched canvas which Hootoksi and the village women painstakingly embroidered and embellished with colorful beads and buttons. The horizontal rotor shaft was coupled to a vertical output shaft by two sets of pulleys and V-belts so that one turn of the windmill blades resulted in a turn of the pulley at the bottom of the tower. I chose belts over bevel gears because belts would permit a certain amount of slippage in case the machinery being driven by the windmill ever jammed, bringing the windmill to a stop before its mechanism was destroyed. Gears, on the other hand, would be stripped of their teeth. The windmill rotor and drive was mounted on a 20-foot high steel tower and was free to turn on ball bearings in any direction to face the wind.

Tilonia’s desert climate required that the windmill work effectively even at low wind speeds, typically 12 Km/hour. However, there were frequent seasonal thunderstorms and high winds which could destroy a windmill built for low speeds. Furthermore, I had designed a high solidity rotor (i.e. a rotor with many blades for greater exposure to the wind) in order to supply the high starting torque (power to turn the load) generally required by agricultural machinery.

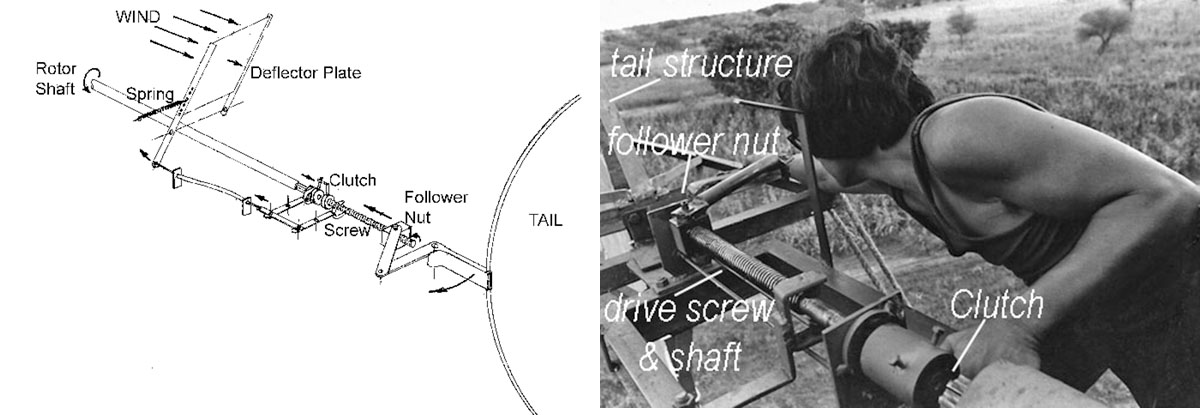

This type of rotor is more vulnerable to storms than other rotors, As storms and high winds are not uncommon in Tilonia, this presented a problem that had to be tackled early on in the design. I solved it by designing the tail fin to swing sideways by up to 90 degrees off axis if the wind pressure exceeded a certain threshold, causing the windmill to turn away from the wind. In a storm, the force of the wind made a plate swing backward against a spring. This engaged a clutch which connected the rotor shaft to a screw. The screw turned and forced the tail to swing outward in an arc and finally disengage the clutch. The screw kept the tail locked in the "off" position until someone reset it.

This type of rotor is more vulnerable to storms than other rotors, As storms and high winds are not uncommon in Tilonia, this presented a problem that had to be tackled early on in the design. I solved it by designing the tail fin to swing sideways by up to 90 degrees off axis if the wind pressure exceeded a certain threshold, causing the windmill to turn away from the wind. In a storm, the force of the wind made a plate swing backward against a spring. This engaged a clutch which connected the rotor shaft to a screw. The screw turned and forced the tail to swing outward in an arc and finally disengage the clutch. The screw kept the tail locked in the "off" position until someone reset it.

Below is a diagram of the mechanism:

The windmill was connected to a pump which lifted water from the SWRC’s huge central well on which the windmill superstructure was mounted. I understand that over the years grain grinders and a variety of other agricultural machines were tested with it. The total cost of the windmill including the tower, transportation and all the experimental work, was 13,000 Rupees, then less than 1000 US dollars.

The windmill was connected to a pump which lifted water from the SWRC’s huge central well on which the windmill superstructure was mounted. I understand that over the years grain grinders and a variety of other agricultural machines were tested with it. The total cost of the windmill including the tower, transportation and all the experimental work, was 13,000 Rupees, then less than 1000 US dollars.

When I left India for Bhutan five years later, I heard that the windmill was still in operation. Someone in Bharat Heavy Electricals Ltd. (BHEL) got wind (no pun intended) of what was happening in Tilonia. A team of engineers from BHEL’s Energy Systems and New Products Division headed by Dr. H.N. Sharan was dispatched and a report entitled Techno-Economic Evaluation for the Tayabji Windmill was prepared. The report concludes as follows:

Based on general observations and on the performance evaluation results, following comments are being made:

Tayabji windmill is of a simple design and has been constructed with indigenously available materials. It has an extremely simple and effective luffing mechanism for the safety of the windmill against possible occasional high wind velocities. The materials used for sails are cheap and sufficiently durable.

The windmill has a high starting torque and is quite suitable for direct applications for pumping water, grinding and fodder cutting. The unit is, however, not suitable for electrical generation.

The pumping characteristics of the windmill determined at site have differences as compared to performances of NAL (National Aeronautical Laboratory) windmill of WP-2 design.

The cost of the windmill given by Mr. Tayabji of Rs. 13,000 is approximately correct and with additional modifications and additional tower structure, it will not exceed Rs. 15,000 for large scale production.

In the recommendations, the report states

Although the performance of the windmill of the existing design compared to NAL (National Aeronautical Laboratory) windmill of WP-2 design is not very good, the low-cost aspect of the design itself is a sufficient criterion for continuation of further work on the development of the windmill to make it more efficient, without increasing the cost excessively. A number of aspects will have to be looked into in a more detailed manner for improving the performance. This further work can possibly result in a low-cost windmill suitable for rural applications where wind velocities are sufficient and have a range of around 10 to 15 km/hr.

WIND PUMP, MAHARASHTRA

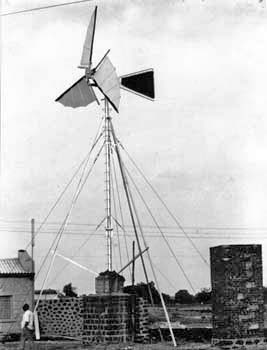

A couple of years later, Drs. Raj Arole and Mabelle Arole who had established the Comprehensive Rural Health Project in Jamkhed, Maharashtra State, and who were later both awarded the Ramon Magsaysay Award, asked me to build a windmill to provide water for the hospital from a deep borehole nearby.

A couple of years later, Drs. Raj Arole and Mabelle Arole who had established the Comprehensive Rural Health Project in Jamkhed, Maharashtra State, and who were later both awarded the Ramon Magsaysay Award, asked me to build a windmill to provide water for the hospital from a deep borehole nearby.

I seized the opportunity to design an entirely different and more efficient machine utilizing the Tilonia unit’s low-cost features along with BHEL’s design recommendations (which in fact applied more to the type of dedicated windpump that CRHP was looking for than a multipurpose windmill).

I seized the opportunity to design an entirely different and more efficient machine utilizing the Tilonia unit’s low-cost features along with BHEL’s design recommendations (which in fact applied more to the type of dedicated windpump that CRHP was looking for than a multipurpose windmill).

The windmill had 3 canvas blades and used a crankshaft to operate a reciprocating pump rod connected directly to a cylinder deep inside a borehole. The unit was mounted 20 feet above ground on a steel pipe supported by guy wires. While no formal technical evaluation was carried out, it was evident that it worked much more efficiently as a windpump than the Tilonia unit.

These windmills could not have built without the invaluable help and expertise of Avtar Singh "Nata" who was also instrumental in helping to bring the filmstrip kit to fruition.